As spooky season creeps in, you might find yourself searching for ways to set a chilling mood. Classical music can easily deliver a tingle down your spine, whether it’s “Danse Macabre” or “Night on Bald Mountain.” But what about the stories that haunt the classical music world? These five mysteries are sure to leave you shivering in fright, just in time for the spookiest night of the year.

The 18th-century true-crime story of Jean-Marie Leclair

In the 18th century, a time of buckled shoes and powdered wigs, it was a lot easier to get away with murder and conspiracy than it is today. Jean-Marie Leclair was a violinist and composer with a successful career, complete with commissions from kings and princesses, and is credited with establishing the French school of violin.

But floating that high in society is bound to put a target on your back. On the night of October 22, 1764, Leclair was caught in a dark Parisian alleyway by someone out for blood. His cold body was found the next day, stabbed to death. Suspicion fell on Leclair’s estranged wife, whom he had left six years prior. Could she have killed Leclair, in hopes of claiming his money and property? Or was it his jealous nephew, desperately wanting Leclair’s success as a violinist? The mystery remains unsolved to this day.

Rosemary Brown, the woman through whom long-dead composers rose

Picture this: you’re a bright child of seven years, and the world has been good to you. One day, as you play in your nursery, goosebumps rise on your arms. The sunlight streaming through the window fails, with only a pale blue glow filtering through. You jump at the sight of a man standing before you, but he feels only as tangible as a whisper. He tells you that he will make you a great composer someday. You want to ask him who he is, what he could mean by that, but he vanishes without a trace. Though your cozy nursery becomes warm and sunny again, you can’t shake the chill from your shoulders.

Although the ghost of Liszt reportedly approached English medium Rosemary Brown in 1923 when she was seven years old, it wasn’t until her late forties that Liszt returned, flanked by Beethoven, Schubert, Debussy, and many others. Brown’s mission? To take these ghosts’ music from beyond the grave and share it with the world of the living. Some composers kept their distance, dictating notes to her as she wrote, while others took control of her hands, playing their music through her at the piano. Brown stirred a lot of attention in the 1970s and ‘80s with her stories of decomposing-composer possession, and the general consensus of whether her ghostly encounters are credible remains split.

Carlo Gesualdo’s blood-fueled jealousy

Italian composer Carlo Gesualdo is a perfect example of when a brilliant mind is also a cruel mind. Working in the late 1500s and early 1600s, Gesualdo largely composed madrigals and sacred music, employing a chromatic style that put him far ahead of his time as a composer. However, he was in every other way a man of his time, benefitting from the privileges of being wealthy, of noble birth, and male.

And what does a man of that time do when he discovers his wife is having an affair? Gesualdo’s wife, Donna Maria d’Avalos, and her lover, an area nobleman, ultimately met a bloody and untimely end, and Gesualdo’s reaction to his wife’s affair is horrifying by today’s standards. One night in October 1590, Gesualdo took it upon himself to murder both his wife and her lover in flagrante — that is, in the act. His shocked servants reported that, even after he already very definitely murdered them both, Gesualdo went back into the room with his bloodstained knife to make sure they were really dead. Although there was no question of “whodunit,” the Grand Court of Vicaria in Naples ruled that the jealous composer had not committed a crime. Gesualdo walked away free, and he married again seven years later.

Franz Joseph Haydn lost his head

Imagine being so greatly admired for your artistic talents that two people would steal your head, hoping to understand what makes it so special. This very act of thievery happened to the great composer Franz Joseph Haydn shortly after he was buried in May 1809. The thieves, one a former secretary to Haydn’s own employers and the other a governor of a provincial prison, recruited a gravedigger to exhume Haydn’s recently buried body, cut off his head, and bury him again. As long as no one else wanted to dig him up again, none would be the wiser.

Of course, 10 years later, Haydn was exhumed with the intention of being reburied with the Austrian Empire’s royal family. You can imagine the outrage when Prince Nikolaus II, a patron of Haydn’s, discovered Haydn’s skeleton lacked a skull. Though the thieves were pursued, they were clever enough to keep the skull hidden from authorities, willing it to other prominent figures, who willed it on further. One hundred forty-five years passed before Haydn’s skull was finally returned to his body, complete with a celebration to mark the occasion, bringing the burial process to a satisfying, long-overdue end.

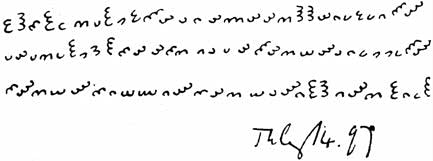

Elgar’s uncrackable Dorabella Cipher

Edward Elgar left behind a few puzzles after his death in 1934, one of the most famous being the Dorabella Cipher. He wrote it for the daughter of a friend, and it remains unsolved to this day. Many have tried to crack it, their interpretations ranging in clarity from pure gibberish to vague well-wishes for the daughter. One, by cryptographer enthusiast Richard Henderson, reads:

whY AM I VERY SAD, BELLE. I SAG AS WE SEE ROSES DO. E.E. IS EVER FOND OF U, DORA. I kNOw I PeN ONE I LOVe. All Of My Affection.

In 2023, someone put the cipher through some computer algorithms built to solve these kinds of puzzles, and not even the computer could figure it out. Another expert cryptographer has argued that the cipher isn’t even supposed to translate into words, but rather into music notes, forming a melody. Take a look at it for yourself, and let us know if you have any idea what Elgar could be trying to say.

Love the music?

Show your support by making a gift to YourClassical.

Each day, we’re here for you with thoughtful streams that set the tone for your day – not to mention the stories and programs that inspire you to new discovery and help you explore the music you love.

YourClassical is available for free, because we are listener-supported public media. Take a moment to make your gift today.